Post and Courier

5/2/2021

By David Slade dslade@postandcourier.com

https://www.postandcourier.com/news/all-public-housing-in-charleston-to-be-replaced-or-renovated-in-sweeping-initiative/article_d7aa9a52-93dd-11eb-842d-63dd1fa73cf9.html

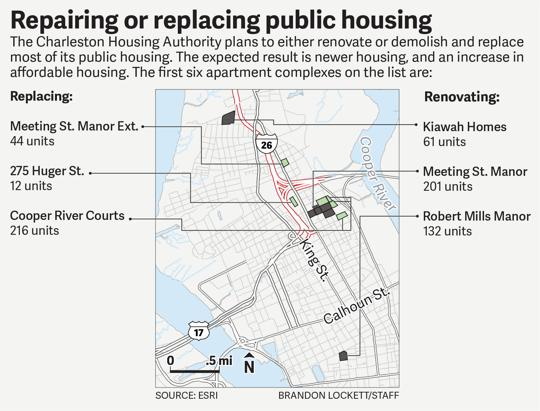

A bold plan to renovate or replace all of the Charleston Housing Authority’s public housing has started, and it’s expected to add 800 to 1,000 affordable apartments to the city.

Existing complexes and buildings with a combined 1,407 apartments will either be extensively renovated or demolished in order to build larger buildings on the same properties.

“It’s huge,” Charleston Housing Authority CEO Don Cameron said. “It’s going to change everything.”

No low-income housing will be lost, more housing will be created, and tenants who are displaced during renovations or construction will be able to return to the same properties, Cameron said.

The most visible changes will be seen on the Charleston peninsula where some of the CHA’s apartment complexes cover multiple city blocks.

The authority owns 56 properties throughout the city — on the peninsula, West Ashley, James Island, Johns Island and Daniel Island — and one in Mount Pleasant, but the peninsula used to be the city limit and that’s where the oldest and largest complexes are located.

The renovate-or-replace initiative could take up to a decade to complete and cost hundreds of millions of dollars, but the money won’t come from CHA or local taxes. Each apartment complex or building will involve a public-private partnership funded largely through state and federal low-income housing tax credits.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development created the financial framework years ago, called the Rental Assistance Demonstration program, and Congress approved it in 2012. The RAD program aimed to use tax credits to get private developers involved in building and renovating public housing, and that’s happening, but in this case the CHA will continue to own all the properties.

Work is expected to begin this year on the first two apartment complexes on CHA’s list. The 12-unit apartment buildings at 275 Huger St. will be demolished to make way for an 85-unit complex, and the 61-unit Kiawah Homes complex in Wagener Terrace will be renovated.

“We’re using this (275 Huger) as an experiment for us to learn how to do this so we can use it as a model when we get to the bigger properties,” Cameron said. “I think the trust in the community has got to be good that what we say is what we do.”

Patricia Stewart, chairwoman of the CHA’s Resident Advisory Board, said the authority’s plans have been hard to understand, creating some anxiety among tenants.

“People are still anxious about the fact that things are changing and they wonder if it will benefit them,” she said. “The people are so concerned. We’re all still waiting to see what it turns out to be.”

For years, public housing tenants and advocates have feared that the rapid gentrification seen on the peninsula would lead to public housing being eliminated. Cameron said the opposite is happening, that there will be no loss of housing and there will in fact be more.

“I think it’s a good idea as long as the residents can come back,” said Kathy Nelson, secretary of the Resident Advisory Board.

Expansive apartment complexes that have been in place on the Charleston peninsula since the 1930s or 1940s will be renovated or replaced. They include two adjacent projects — Cooper River Courts and Meeting Street Manor — that together are home to 417 families.

Those low-rise apartments occupy more than seven blocks between Meeting Street and Morrison Drive near Sanders-Clyde Elementary School.

The Housing Authority’s plan is to renovate apartment complexes that were well-built and rent well, including Meeting Street Manor and Robert Mills Manor.

“They’re built like bomb shelters,” said Cameron, praising the quality of construction. Meeting Street Manor was built in the mid-1930s as a Works Progress Administration project and is the oldest public housing in the state.

The renovation projects are expected to cost $45,000 to $100,000 per unit, Cameron said. In most cases, some tenants will relocate during the work, but most will move from older units to newly renovated ones as work is completed.

The federal government is picking up most of the tab but in a complex and indirect way.

First, the CHA will find partners that can benefit from low-income housing tax credits — something the authority can’t do because it’s a government entity. The tax credits pay out over 10 years, but once they are approved, the developer typically sells them at a discount, usually to banks, and the proceeds fund a large portion of the costs of renovations or demolition and construction.

For example, the demolish-and-replace project at 275 Huger St. is expected to cost $23.2 million. Tax credits are expected to cover about $10 million of the cost, and rents collected over time should pay off the debt that will cover the remaining costs. The housing authority will continue to own the land and will eventually own the new buildings.

The low-income tenants that live at 275 Huger now will have the right to return when the new buildings are completed, but there will also be 73 additional apartments. Most will be for low-income tenants, but 22 would be rented at close to market rates, making the new complex more financially sustainable.

The renovated or new apartment complexes would be assigned “project-based vouchers” — federal rent supplements that are tied to those apartments. The vouchers pay most or nearly all the rent for people with low incomes, who typically contribute 30 percent of their incomes toward the rent and utilities.

Market-rate apartments that could be included in new buildings are meant to serve as “workforce housing” and are not subsidized, but there may be maximum income limits for potential tenants and the rents are typically below those on the open market. The idea is to provide housing for people with moderate incomes who work nearby.

Part of CHA’s goal is to replace some low-income housing complexes with modern apartments that will house an economic mix of tenants. The CHA already operates one such building on the peninsula, the recently built Grace Homes apartments at Meeting and Cooper streets, which has 35 income-assisted apartments and 27 workforce housing units.

At Grace Homes, unsubsidized two-bedroom workforce housing apartments rent for $1,327. Low-income apartments in the same complex are subsidized, with federal housing vouchers that pay some of the tenants’ rent and utilities — whatever amount is left after the tenant contributes 30 percent of their income.

The new CHA complex planned at 275 Huger St. will also have some workforce housing units, which won’t be subsidized but will have rents lower than those nearby, Cameron said. Just across the Huger Street, at East Central Lofts, a 731-square-foot 2-bedroom apartment rents for $1,765.

Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg touted the CHA initiative in his recent State of the City address, saying: “We’ve given our Housing Authority the go-ahead to work with the federal government to replace or rehabilitate every public housing project in the city — an initiative that will both increase overall housing supply and give our public-housing residents a safer, cleaner, better place to live.”

Even on the Charleston peninsula, the Charleston Housing Authority does not own all of the public housing. Some apartment complexes are owned by for-profit or nonprofit companies, and they are not part of CHA’s plans.

For example, the county’s housing authority owns Joseph Floyd Manor, the troubled high-rise complex on Mount Pleasant Street. And 300-unit Bridgeview Village, the single-largest low-income housing complex on the peninsula, is owned by nonprofit Housing on Merit and managed by Standard Communities.

The plan to renovate or replace all of CHA’s public housing units is set to begin later this year with the one demolition and replacement project and one renovation. Kiawah Homes will be the first. The work at 275 Huger St. will take longer because a new building must be designed and permitted, so residents there will not move out before the start of 2023.

Kiawah Homes was built in 1942 and is a collection of duplexes. Extensive renovations there are expected to cost about $100,000 per unit, Cameron said, and could begin in August.

He said counselors have met with all the residents there to explain what will happen; mainly that some residents — maybe a third of them — will be relocated during renovations while others will move within the complex as renovations are completed.

When the Kiawah Homes and the 275 Huger St. projects are done, the housing authority can take what was learned from those first efforts and move on to some of the more than 1,300 apartments remaining.

By the end of the year, CHA hopes to be seek a developer for work on the demolition and replacement of Cooper River Courts.

Reach David Slade at 843-937-5552. Follow him on Twitter @DSladeNews.